Kayaking in Sea of Cortez: Where Are All the Fish? – Day 17

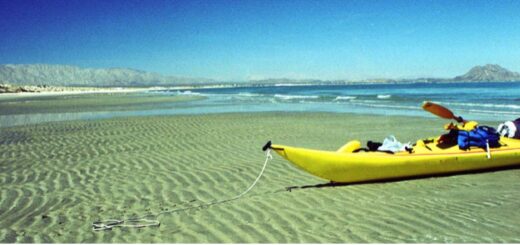

I woke early on the beach in front of Guillermo’s, Bahia de Los Angeles, thinking all night about the way to re-pack my new supplies so they would fit into the kayak. I threw away some stuff: an old backpack and a wimpy flashlight that I had (I found my good one). In the morning, there was no hot water for showers, so I skipped that and put the kayak in the water at about 6:30 AM. The wide bay was quite calm as I began kayaking in Sea of Cortez and crossed about 4 miles to the other side. There were several whales deep inside the bay and I came within about 50 yards of one that surfaced several times near m

I went about two hours and stopped just the other side of Gemelitos Island. The water seems to be brown again with lots of small particles. When I got around the outside point, called Punta Don Juan, the water turned blue again. At one of the areas that I passed through, there was drifting algae in thin films, so thin I couldn’t catch it in my hand. I stopped a couple times to rest and then for lunch near Punta El Alacran. As I was going around one of the points composed of lava rock, I spotted a bobcat slowly walking along the base of the cliff. Apparently, he was unconcerned about me in the kayak because I was able to slowly paddle along the shore and watch him on his patrol. It’s rare to see a bobcat. I think I have only seen another one in my whole life.

I picked up some drifting seaweed to see what was on it, which I do from time to time. I usually find small shrimp or crabs but this time I was surprised to find a bunch of little planaria worms that fell off the seaweed on to my deck. They were all about 1/8-1/4 in. long, without a real head shape, but they moved around like planaria. I guess they are helping to break down the plant material after it gets loose and is beginning to decay. Planaria are primitive flatworms that inhabit freshwater and marine environments. Planaria have phenomenal regeneration abilities, with some documented to regenerate from just 1/200th of a piece when separated from the main body. If the head is separated from the body, then the head piece will grow another tail, with the separated body growing another head. I washed them off my deck after watching their movements for a while.

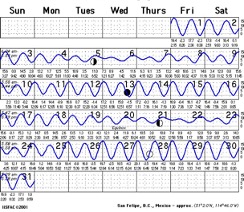

It was flat calm most of the day, and it got hot before some clouds came in to cool it down. There was a new moon developing, so the tides were quite minimal. It is amazing how quickly the waves die down when the wind stops and makes for fantastic kayaking in Sea of Cortez. Of course, the waves also come up very fast when the wind starts blowing.

I saw a new bird for me today, Xantuse’s murrelet, very cute little guys. There is a Baja form with white around the eye, but I didn’t notice any white when I got close to several murrelets on the surface. These seabirds feed in deep ocean waters on larval fish like anchovies and sardines, as well as small crustaceans and various aquatic invertebrates. Murrelets are wing-propelled divers, flying underwater after prey with powerful, rapid wingbeats.

I stopped for the evening at 3:30, on a sandy beach about a mile into Bahia Las Animas. I cooked a dinner of Spam and canned corn. While eating dinner I gazed across the sea at the mirages that make the islands to the southeast look flat on top like Monument Valley. I think the more distant island was Tiburon, about 40 miles away, but distorted by the mirage so it appears to be above the horizon.

I think I’ve done about fourteen or 15 miles today, and I’m tired. I’ve been sitting in the kayak for hour upon hour and my tailbone has begun to get sore. I’ve had to make several stops just to get a break from sitting and to relieve the pain. I have been paddling for about 2 1/2 weeks, so I guess something must wear out. I had already adjusted the seat position but that didn’t seem to work. I rolled up my ground cloth and sat on it for the last half-mile or so. The folded ground cloth seemed to work very well and relieved the pain.

While doing my usual beachcombing along the stretch of beach where I landed for the night, I was surprised to see how many porpoise skulls there were. I collected about eight and brought them back to my camp where I set them up in a little circle. With so many skulls on this beach, I presume they were killed in gill nets or by the purse seiners that work this area. I began to think about how there were so few fish jumping, and I had not seen any of the massive feeding frenzies that the Sea of Cortez was notorious for. I had read the early accounts by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in the book “Log of the Sea of Cortez” which described the unending schools of fish. I had seen the wrinkled and faded pictures of the giant Totuava, once caught daily by the score near San Felipe. I have been traveling for seventeen days in this fisherman’s paradise and I have seen hardly any fish. Where have all the fish gone?

Over the last couple of years, I had read many articles about the decline of fisheries in the Sea of Cortez. There are many theories about the cause. One theory is that the dams on the Colorado River, most of them built as make-work projects after the great depression, had stopped the flow of nutrients and silt into the northern Sea of Cortez. Over time, it was thought, the lack of nutrients would result in a decline in the productivity of these waters. If that is the cause, there is some hope, because the dams are silting up and eventually the silt and nutrients will start flowing again.

The theory given most weight though, is that intense fishing over the last 30 years or so has cleaned out just about everything. The Sea of Cortez seems so large to me in my small kayak and there were so few people that it’s hard to believe that fishing could have such an impact. But I had watched the trawlers dragging their nets hour after hour; methodically altering their course to make sure that no spot escaped their catch. The otter boards pulled the nets wide and the cables at the bottom of the net scoured the bottom and captured everything in its path. People on the Baja side of the Sea of Cortez complained that fleets of unlicensed and ungoverned trawlers from the mainland have eaten into the livelihood of local fishermen and caused a massive decline in the number of fish. Local fishermen, who once used hooks and lines, now almost exclusively use mono-filament gill nets that effectively capture every near-shore fish that is moving up and down the coast.

With these thoughts, I arranged the porpoise skulls in a circle that I thought might attract the attention of a passerby someday (who knows when?). At the center, I placed a note in a clam shell with my thoughts:

“Ricketts and Steinbeck, where are you?

No birds are diving, no fish are jumping.

The banquet is over, I fear.

The Sea of Cortez is dying.”

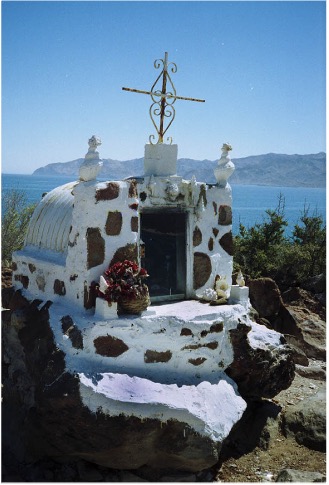

Here in Bahia Las Animas, there was constant panga traffic going to and from the long-established fish camp that takes the name of this bay. Before dawn, the high whine of outboard motors could be heard leaving the fish camp and traveling miles up and down the coast to where gill nets had been set. Early in the morning they would start retrieving and resetting the gill nets. The fishermen slept on the boat during the middle of the day and retrieved the nets one more time before going home in the dark. Sometimes, when they had engine trouble or when the winds came up unexpectedly, they would not make it home until late in the night, or perhaps not until the next day. On top of a rocky point near the fish camp, the fisherman’s wives had built a shrine where they lit religious candles and prayed for the safe return of their men.

When the sun went down in the evening there was a beautiful sky to the east over the islands, it was pink on pink. With my new supply of food, I had some bed-time snacks: coffee with cream, tortillas with jam. My body was craving sweets, I can’t just stop with one tortilla with jam, got to have two.

After I get into the sleeping bag, I usually spend an hour or so with my head out of the door of the tent looking at the stars and counting satellites. I can’t see them by eye, so I searched the sky with my binoculars. This night I saw four satellites, two were going west-east and two were going on the polar route. There must be hundreds of satellites up there and they go around every 90 minutes or so, so they come by frequently. The night sky here in Bahia Las Animas was beautiful.

Next: Day 18 – God Must Live Here!

Please comment on Two Miles to the Horizon.

Back to the beginning of Two Miles to the Horizon

3 Responses

[…] Next: Day 17 – Where Are All the Fish? […]

[…] Day 17 – Where Are All the Fish? […]

[…] Next: Day 17 – Where Are All the Fish? […]